With an organization named “Cheetah Conservation Fund,” it is logical to assume the topic of conversation is all cheetahs, all the time.

In fact, that is not the case, as Brian Badger, Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) director of conservation and outreach, explained during his April 25th visit to Fossil Rim Wildlife Center. There are a lot of facets to CCF’s operation, which can steer discussions elsewhere.

Based in Namibia, Africa, CCF was founded in 1990. Its beginning actually coincided with the birth of Namibia – located in southwest Africa – as a nation.

Badger promptly dispelled the “cheetahs only” notion.

“Despite the name, we don’t focus only on the cheetah,” he said. “It is our aim to keep the cheetah in its natural habitat and secure the wild population, but the key to the success of nature and the planet is balance among all species.”

Cheetahs were, in fact, the focus of his presentation initially. The fastest of all land animals, the cheetah can run up to 70 mph.

“It has a huge stride – up to 22 feet at full speed – and takes up to three strides per second,” Badger said. “It can go 0-60 mph in three seconds – faster than a Ferrari. The cheetah’s main defense is its speed to run away, but that doesn’t work for cubs.”

Sadly, Badger said that only about one in 60 cheetah cubs in the wild will reach sexual maturity.

“It is an amazing cat, but it has lots of enemies in the wild – lions, leopards, hyenas, jackals, hunting dogs – even a group of vultures can steal a cheetah’s meal after it hunts successfully,” he said.

Currently classified “vulnerable” by the IUCN, cheetahs could formally become “endangered” in the near future. There are thought to be about 7,100 cheetahs in Africa and up to 100 in the nation of Iran. Badger said Namibia is the “cheetah capital of the world.”

“There are more cheetahs in Namibia than anywhere else in the world,” he said. “We have about one-third of the world’s population. The vast majority are concentrated in the more fertile land that lies between two deserts. There are many farms and ranches in this area, which lead to human-wildlife conflict.”

Badger said 95 percent of Namibian cheetahs live on commercial livestock farms and ranches that raise sheep and cows. In fact, 80 percent of all the wildlife in Namibia lives on these ranches.

Badger continually stressed the importance of education among the locals in regard to protecting the wildlife.

“A common issue throughout Africa is a lack of education,” he said. “It often leads to inherent bad habits in the way the people are dealing with the wildlife. They aren’t adapting to change on their own. It really helps us to go visit farmers and engage with them and explain why we need their help.

“Education is the basis of everything. We reach about 20,000 Namibians per year through outreach efforts. It’s continual so we create the habits of the future.”

Badger talked about farmers using cage traps to catch cheetahs, yet also how growing education regarding the cats helps keep them from being killed.

“Cheetahs are nomadic with huge ranges that can overlap, so they choose particular ‘play trees’ as marking posts and just can’t resist investigating these trees,” he said. “Farmers put a cage trap by a play tree, surround the rest of the tree with acacia bush and the cheetah will step into the trap; there’s no bait needed, so these traps only catch cheetahs. We’ll get a call from a farmer saying they have a cheetah in a trap.

“We are glad they cared enough to contact us. We’ll go get it, and release it in a different location. The farmer is satisfied with our efforts, plus the cheetah survives.”

Badger said Namibia is 2.5 times the size of California with a population of 2.1 million people, so there is an abundance of open space and thus the CCF does not want cheetahs left in traps for long in the heat without water.

Even with the “open space,” habitat loss is a factor against cheetahs and other wildlife in Namibia.

“When you consider climate change, slightly less rain in Namibia can mean the death of many plants and animals,” Badger said. “A desert country that depends on all of its rain during three months of the year is adversely affected a lot more than a country like England, for example.”

Poaching is not a major problem for cheetahs like it is for elephants or rhinos, but poaching of prey species can contribute to cheetahs targeting livestock. This is a habitat loss of sorts, because cheetahs are drawn to an area they would not otherwise focus on.

CCF utilizes a method to combat the cheetahs targeting livestock that allows the cats to live.

“We developed the livestock guarding dog system, which uses Anatolian shepherd dogs,” he said. “They are rugged, large and very strong, plus they have good sight and hearing to protect livestock. The puppies grow up amongst goats and sheep, so they see the goats and sheep as their family. That makes the dogs brave, loyal and protective.

“A predator wants an easy meal; it doesn’t want to fight another predator. These dogs are an early warning system and take away the element of surprise, so the cheetah heads off to eat what it’s supposed to eat. We’ve trained about 700 of these dogs and placed them in Namibian farms.

“We commit to the farmer for that particular dog’s entire life with monthly visits during at least its first year to check on the dog and maintain engagement with the farmer. If we get a call from a farmer about a non-cheetah, we will still try to help. If we save that animal while helping the farmer be successful, then he is more engaged and open to learning from us; everyone wants results.”

It is interesting that making farmers financially invest in the dogs has benefited their level of care.

“We used to just give the dogs to the farms, and also go collect mistreated dogs,” Badger said. “That has changed. The farmers don’t buy the dog; they buy into the system for $70 American dollars. That investment has helped ensure that these dogs are almost never mistreated anymore.”

The bottom line is the livestock guarding dog system gets results.

“There’s a reduction of livestock lost to predators by 80-100 percent,” Badger said. “It’s a no-brainer. The farmers are coming to us now, instead of vice versa, because it’s a proven system. We have helped to start this system up in Tanzania, Botswana and Zimbabwe. It’s starting to be used in Texas, as well.”

The CCF also trains dogs to find and identify cheetah scat (fecal matter). DNA can be extracted from these samples, so the cheetah does not have to be physically caught to do genetic testing and diet analysis. Also, dogs can match similar scat samples from a large group, which saves time and money that would otherwise go into lab testing.

“When needed, we do run the only fully-functional genetics lab in Namibia,” Badger said. “So, we have many samples to help us learn about different cheetahs. We also use satellite collars on cheetahs for some of our research. We have been doing research since CCF began; 27 years of data can give you real (legitimate) models.”

While Anatolian shepherd dogs are used to protect sheep and goats from predators, when it comes to cows, Namibian farmers turn to donkeys to keep predators at bay.

“The dogs are too small to be amongst cows, so donkeys are their protectors,” Badger said. “You raise the donkeys around cows – a female donkey is incredibly protective. It’s a good warning system because they make a lot of noise.”

Badger also transitioned from animal to plant, as he delved into how acacia bushes are a major factor in the CCF operation.

“You definitely have to consider habitat loss due to the encroachment of the acacia bush,” he said. “At 20 feet tall and wide with huge thorns, the acacia is the biggest cause of desertification in Africa.

“Increasing drought from climate change and overgrazing allow the acacia to take over. Plus, the loss of the megaherbivores – elephants and rhinos – as well as less frequent naturally occurring fires, are not adequately clearing out old vegetation and allowing new growth (of desired plants).”

While this is troubling, Badger pointed out the importance of not overreacting in response.

“The more the acacia bush takes over, the less grass, and then the more land is needed to feed the herbivores,” he said. “But don’t overreact, the acacia bush is supposed to be there. It’s not an alien species; we just need to manage the amount of them.”

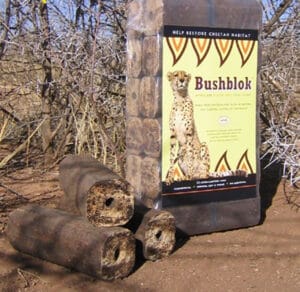

On that note, CCF started a company called “Bushblok” to manage the acacia bushes while improving habitat for cheetahs and other Namibian wildlife.

“We go in and harvest the bushes, instead of eliminating,” Badger said. “Our golden rule is ‘if you can fit your hands around it, it goes.’ Anything bigger than that stays, which means we don’t harvest the mature bushes. After drying them in the sun, we put the harvested bushes into a wood chipper, and then transport the chips to our processing plant at the CCF center.

“Next, we dry the chips. The chips are then grinded into a fine powder, before high pressure and high heat bond the chips through extrusion. The resulting fuel logs burn at high heat with low emissions.”

Processed and sold by Namibians, Bushblok is available in Namibia and adjacent South Africa.

“Unemployment in Namibia is quite high at 30 percent; we only employ Namibians,” Badger said. “We are using unrefined Bushblok to create the electricity for our processing plant with a biofuel generator.”

Badger said Namibia is very forward-thinking in regards to conservation of all sorts.

“It’s the first-ever country to address conservation in its constitution,” he said. “Other African countries that have overreacted on conservation decisions with bad results are now looking to Namibia as a model, since the majority of operations there are going well.”

In so many ways, CCF tries to better the lives of Namibians.

“We set up workshops so they can make jewelry and crafts to sell,” Badger said. “We set up dairy herds and taught them how to make various types of cheese. We set up hydroponic gardens and taught Namibians how to operate them. The common theme is helping the people of these communities develop valuable skills.”

While the cheetahs, other wildlife and citizens of Namibia remain the heart of CCF’s drive as an organization, Badger said it is important to collaborate with people outside the country for continued success.

“We’ve interacted with people in places like the United Arab Emirates, which helps us combat the illegal pet trade, for example,” he said. “We’ve engaged with very wealthy people there and learned a lot.”

A native of England who has been involved with conservation for the last three decades, Badger is currently touring America and enlightening conservationists to the efforts of CCF.

“International support is necessary for CCF to survive,” he said. “I engage with people, try to make them passionate about what we are doing and that’s how you create support.”

To learn more about Cheetah Conservation Fund, check out cheetah.org.

-Tye Chandler, Marketing Associate

May 2, 2017