As one of the most endangered animals at Fossil Rim Wildlife Center, yet also one of the most prevalent at the facility itself, Attwater’s prairie chickens (APCs) require a lot of time from both the animal care and animal health departments.

Director of Animal Health Dr. Holly Haefele discussed the activities and considerations from her department for the coastal prairie grouse.

“At the beginning of the (calendar) year is when we get rolling for APCs,” Haefele said. “In January, we handle all of our adult birds, which is usually 60-70; everyone is considered an adult at that point because almost all of them will breed that spring.”

The avian staff – Janet Johnson and Cara Burch – catch the birds in nets and manually restrains them for individual exams.

“The vet team is there to give physical exams and, just like we would do for a dog or a cat, we look in their ears, eyes and mouth, plus assess body weight and body condition, administer dewormer to kill intestinal parasites and take a blood sample,” she said. “We look for any problems – including specific issues that may have come up in the past for certain older birds. Some of them have been here 8-9 years, so we see ‘old friends’.”

The lifespan for APCs in the wild is much shorter, so some of Fossil Rim’s birds definitely live a long life.

“About two-thirds of our chicks each year hatch and then head off for release,” Haefele said. “We keep a small portion of them to be breeders for a couple of years. If genetics show that those birds are well-represented in the population, maybe after a good two years of breeding, they might get tagged for release as an adult. There are some birds that may have an issue like never growing good flight feathers, for example, or they have a little arthritis.

“Maybe by the time they are well-represented genetically they are 3-5 years old. We don’t tend to release those birds. A grouse typically lives 2-3 years in the wild, so it wouldn’t be prudent for us to release a five-year-old, because their chances of success are small. Instead, we keep those birds as part of our collection.”

The blood samples are tested for a disease called reticuloendotheliosis virus (REV) that has been a problem in the captive APC population at large.

“REV causes immunosuppression and can also lead to cancer,” Haefele said. “It’s not something we want in our captive flock or released into the wild. We choose January because we want to get those blood test results prior to making breeding pairs for the season. The animal health side of things fades off for a while after until chicks start hatching.”

As for those breeding pairs, they are not made randomly. The Houston Zoo employs the studbook keeper and the Species Survival Plan (SSP) coordinator of the captive breeding programs for the Attwater’s Prairie Chicken National Recovery Plan.

“We get breeding recommendations for the upcoming season based on pedigree and genetics,” Haefele said. “The person who figures the pairs out is actually the studbook keeper for the APC SSP. They have a database of all of these animals; the most unrelated birds get paired to maintain genetic diversity over time.

“Before we make those pairs and disrupt the groups that have been living together for several months, we want to see blood test results. Each pair then has enough time to meet each other and decide if ‘they like each other’. That’s not always the case, and so then we make adjustments.”

Male APCs begin doing their courtship displays known as “booming” in mid-February, females begin to lay their eggs in late March, and then chicks start to arrive in late April.

“When chicks hatch, our role is to assist any of them who are in trouble,” she said. “The biggest tell on if a chick is doing well is whether or not it is gaining weight. Tracking weight begins when they hatch. There are a few potential problems we may need to deal with in the first couple of days.

“Sometimes, we have to correct toes that may not be aligned, which can be a result of something off in incubation, maybe humidity or temperature. We can use masking tape to make little booties and leave them on for a couple of days.”

Haefele said the primary problem for APC chicks can be a “failure to thrive”.

“We see approximately 20-percent mortality in our chicks every year, and the vast majority of that falls into the failure-to-thrive category,” she said. “We think maybe they just don’t recognize the pelleted food as what they are supposed to eat. In the wild, they are chasing tiny insects. We can’t replicate that nutritional requirement with insects in captivity, so we replace it with a high-quality pellet designed particularly for (APC) chicks.

“We support those chicks (in need) medically from 1-6 days, sometimes with fluids injected subcutaneously. Maybe we add antibiotics if there’s an indication that infection might be a problem.”

If APC chicks do not eat, the veterinarians literally take matters into their own hands.

“When we need to do feedings for a 12-20-gram chick, that involves taking a tiny syringe and tube placed into the crop,” Haefele said. “The chick is given a slurry of diet that we mix up each day. It’s force-feeding those that won’t eat on their own. That’s delicate work, but it does help some of these birds survive.

“The light goes on – ‘there is food in front of me’ – and then they start gaining weight normally. Once they get over that 7-10-day hump of mortality, things even out and we don’t see a lot of problems. When these birds transition to being outside and are exposed to bugs and grass, we start routine deworming.”

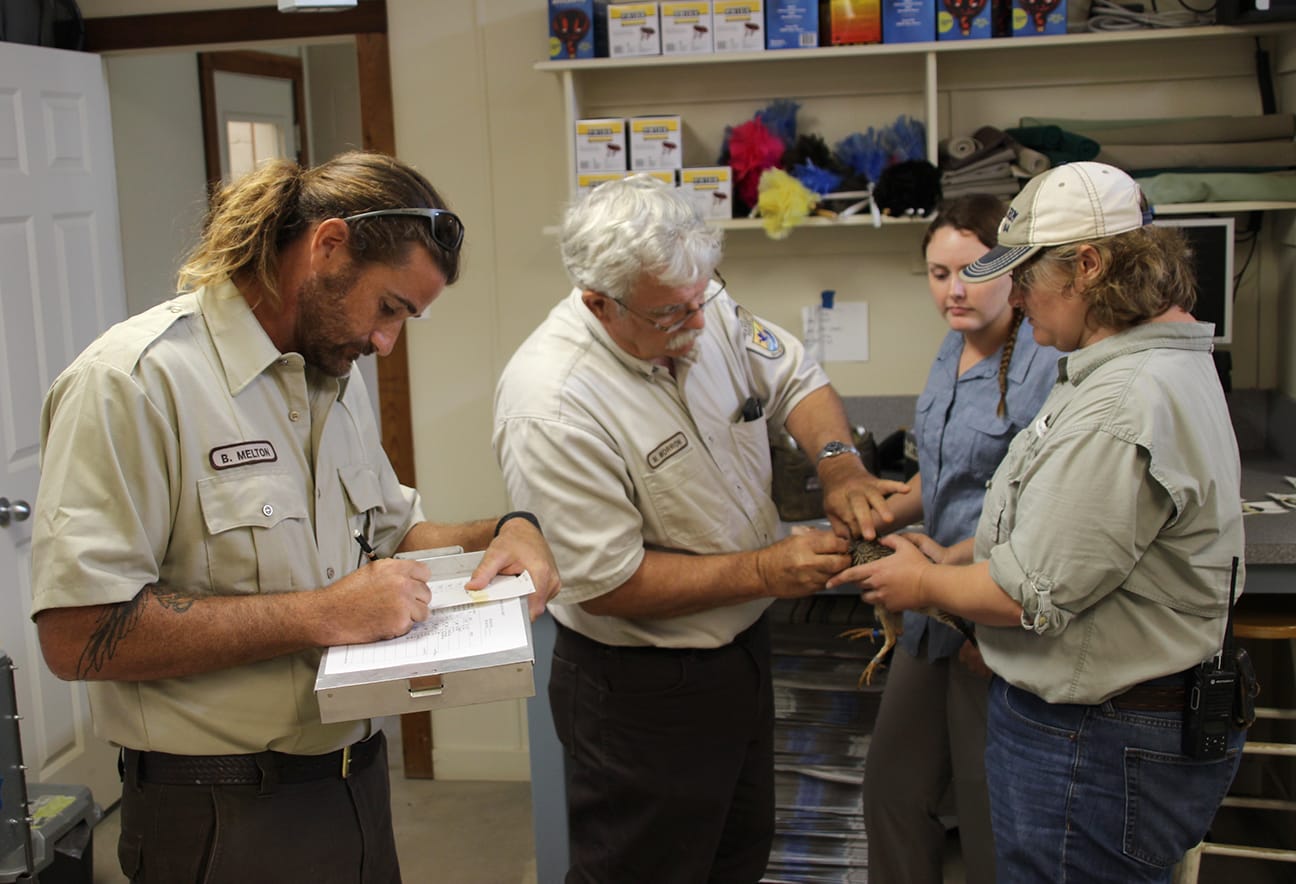

In June, all of the Fossil Rim APCs are inspected again, similar to what occurred in January. This year, it was done in late June.

“It’s an important time,” Haefele said. “After the stress of breeding season and hens cranking out eggs, the males have been booming, which is very intense activity for them. We haven’t had hands on the birds in a while, so we can sometimes find some problems. We were pleased to find that everyone looked really good in terms of body condition with no internal parasites.

“Deworming, as well as blood draws for REV testing, other tests for infection and to get complete blood counts on each individual bird are goals. It is huge for us to say we don’t have any disease problems ahead of the releases.”

While exams on adult birds are fewer and farther between, every chick – there are approximately 280 this year – gets handled each month with a physical exam and dewormer administered.

“We also collect blood when they are about 200 grams for DNA banking,” Haefele said. “The other thing we do is check the chicks for REV. We worked closely with the diagnostic lab at Texas A&M in 2017 to develop a more noninvasive way of doing that. Previously, you could only check with a blood sample or postmortem with a liver sample.

“The lab worked to be able to use a fecal sample instead. So, now we just send that sample off to be tested. It is a lot less stressful on the chicks and easier for us, plus less expensive because we can batch the fecal samples. The vast majority of the 280 are headed to the Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge for release, so we make sure to avoid inadvertently putting that virus out there.”

Speaking of release into the wild, Haefele discussed the pickup days when staff from U.S. Fish & Wildlife arrives at Fossil Rim to transport APC chicks to the refuge. The first of four pickups in 2018 occurred on July 10.

“The refuge biologist – Dr. Mike Morrow – brings his team, and we process the birds that are going to be released at the refuge,” Haefele said. “For the vet team, that means a physical exam, deworming for the birds that are due for it, and identifying any potential problems at that time. If they are too thin, they are going to get pulled off that release list and maybe put back on for one of the remaining 2-3 releases that summer if they can turn (their health status) around.”

The veterinarians also have to be prepared for the unexpected during exams or due to a call they might receive from the avian staff.

“We sometimes run into interesting problems,” she said. “Chicks are very curious, and they like to eat stuff. Sometimes, they get into trouble because they don’t know better. An interesting case this year was a male chick weighing about 65 grams that tried to eat a stick nearly as long as he is.

“It was stuck from his crop to the top of his esophagus. You could tell he was very uncomfortable. I actually reached in his mouth with a couple of people holding him and pulled it right out.

“Sometimes, we see wing fractures or leg fractures we can repair. In the past, it has been a problem when they’ve eaten Bermuda grass that’s gotten stuck in their GI tract, but it’s less of an issue now.”

The veterinarians try to involve their preceptees as much as possible in animal health activities, but handling APC chicks requires great sensitivity.

“In animal health, we don’t handle anything else as small as an (APC) when they start hatching every April,” Haefele said. “Then, you have a tiny bird you are doing procedures on. We are protective of the chicks and don’t even let the vet students handle them because it’s such delicate work.

“We let them do some things with the adults and older chicks, such as deworming and drawing blood. You don’t want to make them too nervous, but you remind them there are only a few hundred of these birds in existence.”

-Tye Chandler, Marketing Associate