When “Meadow” the cheetah was injured in early December, she required a series of casts to help her foot heal properly.

Director of Animal Health Dr. Holly Haefele was appreciative of outside help for the carnivore.

“We were incredibly lucky to have Dr. Chad Marsh come out to Fossil Rim to surgically repair Meadow’s foot,” Haefele said. “Dr. Marsh is a surgeon at Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery in Weatherford. Meadow fractured all four of her metatarsal bones, so a simple cast was not adequate to stabilize her foot. Had only one or two metatarsals been broken, the other bones would have splinted the fractured ones and we could have just cast her ourselves.

“Not only did she need surgical repair, the repair was very challenging because the breaks occurred so distally (near her toes), and there were multiple pieces. The only good option was to place a pin down the middle of each bone, stabilize a few of the bigger pieces with cerclage wire, and place a cast for added stability. We couldn’t have done it without Dr. Marsh and his team’s help, and we are very grateful.

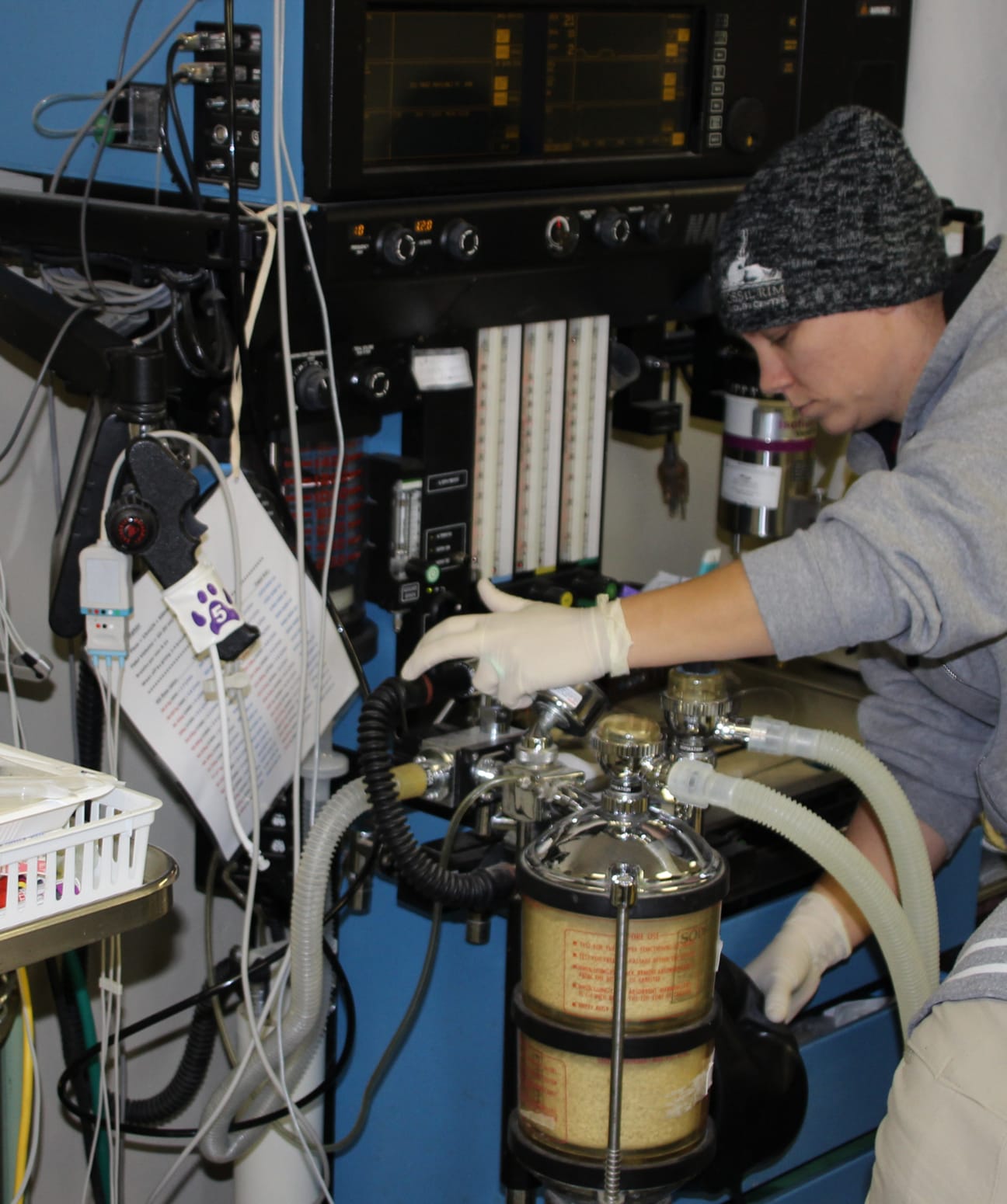

“It was a long procedure, but Meadow’s anesthesia went really well and she woke up nicely, and with some good pain meds on board. Due to the swelling of the foot at the time of initial repair, we had to recast a week later to account for the reduced swelling. We were worried she might try to chew at her cast, but so far, so good.”

As for the recasting a week later, Fellowship Veterinarian Dr. Lauren Schmidt elaborated on her removal of the first cast and application of a second.

“To get a better idea of where Meadow was injured, if you think of a person’s hand, we are talking about the area right above the fingers and below the wrist,” Schmidt said. “When we removed the cast that was applied on the day of her surgery, swelling had dissipated and so the exact same cast design would no longer fit. We had had to manipulate the bones on the surgery day and that agitates the soft tissue in the area.

“We used a cast saw for removal, which is specifically made to cut through the casting material. You cut through both sides and peel them like a clam shell without applying pressure to the leg. In theory, the saw won’t go through soft tissue, but I’m extremely careful that I stop at the cotton padding.”

Regarding Meadow’s second cast, Schmidt explained how the design is decided upon.

“The goal of a cast, and bandaging a leg in general, depends on what the problem is,” Schmidt said. “In this case, we had fractures and some small incisions that were surgically made. At the point of this (second) cast, the incisions were relatively healed, so I wasn’t concerned about applying a layer for them.

“But, typically if you have a wound, you’ll apply a dressing layer with antibiotic cream and maybe a non-adherent bandage over it. That was the route taken for the first cast right after Meadow’s surgery.”

The size of the animal patient can influence how many layers are needed for a cast – in Meadow’s case, three for this cast.

“Once you identify the area you want to bandage and cast, you apply the first layer,” Schmidt said. “You want to keep a contiguous thickness to the cast. If you have thick and thin areas, it can cause constriction or rub wounds in those areas. I start with a soft, cotton-padded wrap that will be several layers for cushioning.

“In areas I think there might be pressure points, I’ll use foam pads. In this case, above and below her hock (joint). Over that, I put more of a pressure layer with brown gauze, which is a cotton roll, but it doesn’t have much flexibility and keeps everything tight and in place.”

“After that, we put on the cast itself, which is fiberglass in this case. When you take it out of the package, it’s very soft and supple. Then, you put it in some warm water to offer more maneuverability as you apply it to the leg.

“As it dries, it hardens on the leg in the position you placed it. One of the goals is to have the cast as smooth as possible. Any lumps or bumps can be felt by the animal and be very irritating, especially since it might be on for weeks at a time.”

How high – and low – the cast goes is a major consideration.

“How far up the leg do you want to bandage it?” Schmidt said. “Typically, if a fracture is involved, you want to immobilize the joints above and below where the fracture is occurring. We made sure to incorporate the hock joint all the way down to the toes, covering the entire foot. We aren’t giving Meadow the opportunity to walk around on wet substrates like mud, which could lead to a lot more irritation.

“We almost always cover the digits in a cast for animal medicine; I’d do the same for dogs and cats. If it is a soft bandage, I’ll usually leave the toes open.

“If the fracture had occurred higher, we would’ve needed to extend the cast potentially all the way up the femur, which is difficult. This fracture location made for a relatively easy area to immobilize.”

An effort is made to minimize irritation caused by the cast.

“It is especially important to avoid rubbing at the point where a cast stops, so she can walk without it being too irritating,” Schmidt said. “She did experience some irritation from the first cast, so we brought the height down on this one. This shorter cast won’t touch the pressure sores that developed from the first one.”

This aspect of veterinary medicine has always been an emphasis for Schmidt.

“This is an interest of mine, so I’ve taken a particular interest in making an excellent bandage or cast early on in my career,” she said. “I know it will be advantageous for me as a skill in the future. I always want to get better at it, but I’m very comfortable doing it. Part of the reason you want a cast to aesthetically look good is because that likely means it will feel (relatively) good on the animal and help it heal.

“That’s why I spent a lot of time rounding out the bottom and making it something (Meadow) can walk on. She’ll be stuck in that position for weeks, so you try to make it comfortable. Would I be comfortable if I were wearing it?”

This will not be Meadow’s final cast by any means, but she is on the road to recovery.

“Traditional fractures in most healthy, adult mammals will take six to eight weeks to heal, which we believe is the case with Meadow,” Schmidt said. “We’ll check this one again in two weeks, and either place nearly the same cast again or downgrade it into a splint. Meadow is handling this fantastically and didn’t try to eat her first cast, which is encouraging.

“The first cast will end up being the shortest interval at one week on, since the swelling went down enough to make that cast loose and increase the rubbing risk. The new cast needed to be more specifically fitted to the current state of the paw without inflammation.”

Meadow was visited by the dentist – actually Veterinary Technician Allyssa Roberts – during the procedure.

“Allyssa was working on the teeth, since there was accumulation of tartar,” Schmidt said. “We didn’t want to do so during her initial surgery, because there were other aspects for us to focus on at the time.”

Cheetah Specialist Jess Rector not only got the chance to help Schmidt apply the cast, but she also gained valuable experience with a blood draw technique known as “tail bleeding.”

“You always hope that others use a surgery or other procedure as a valuable learning opportunity,” Schmidt said. “Jess got to take a blood sample from the tail, and that’s an important method for an animal care specialist that can be used on some awake animals without veterinary staff present. It can allow you to bypass an immobilization and still get a blood sample. A lot of the animals know their (caretaker) really well and are comfortable enough to be a more willing participant.”

Staff will keep a close eye on Meadow in regard to the design of the next cast.

“Since we changed the positioning of the cast and it starts further down the leg, if Meadow does encounter irritation or another issue, we could cut the two-week duration of this cast short,” Schmidt said. “Keeping it from getting wet is important to avoid skin infections underneath. To me, her foot looked really good for how recent the surgery occurred.”

Carnivore Curator Jason Ahistus shared his thoughts on Meadow’s recovery from the animal care perspective.

“In the field of animal care, you never have two days that are the same,” Ahistus said. “Things change constantly, and you have to adjust to the ups and downs and unexpected situations that arise. We continuously monitor the well-being of all of our animals and when these terrible events happen, we do everything we can to help that animal.

“Meadow’s injury is difficult to manage. We have to look at the situation from multiple angles so we can address the injury/healing process, Meadow’s response to medications, and we also watch her behavior to determine if she is stressed or not. We want Meadow’s movements to be as limited as possible so her leg can heal, but cheetahs tend to stress easily in small spaces, so it is a juggling act.

“Luckily, we have a new cheetah yard that was designed for situations just like this and we have several levels of containment. We start with limited indoor space, so Meadow is not too active. As she becomes more capable of increased movement or if she becomes stressed in a small space, we have the ability to offer more space both indoor and outdoor, while still limiting her mobility.

“These decisions are made through collaboration between our carnivore staff and the veterinarians; we communicate regularly throughout this process. We weren’t sure how Meadow would react to the surgery and having a cast, but she has been a great patient and is recovering well. We couldn’t have asked for a better response from Meadow.”

-Tye Chandler, Marketing Associate

I agree with you