When “Alastor” the eastern box turtle was not showing the appetite he usually does at mealtime, Children’s Animal Center Supervisor Kristina Borgstrom decided it was time for a doctor visit.

Before addressing his medical exam, let’s learn a bit more about this box turtle and his species.

“Eastern box turtles are native to East and Southeast Texas – grasslands and deciduous or mixed-forest environments,” Borgstrom said. “There are three species of box turtles in Texas. A lot of turtle populations are diminishing due to habitat loss, urbanization, and deaths from vehicles on the road. Alastor is part of our ambassador animal program.

“When he’s not going out on programs, he’s a display animal that lives at the Children’s Animal Center. We got him in August 2018; we were looking for more animals to add to our collection for diversity, so we figured a turtle would be a fun option to encourage talk about reptiles. Plus, his small size makes it easier to bring him out on a program.

“Obviously, travel isn’t an option for our big African spurred tortoises. We suspect Alastor is probably middle-aged to older.

“His species can live at least into their upper thirties, but not as long as a tortoise. As a full-grown male, he is a little smaller with a flatter shell than the females of the species.”

Alastor used to live at Zoo Atlanta.

“He’s a cool case, because he’s not captive-bred and born,” Borgstrom said. “He’s a wild animal that went through Zoo Atlanta’s wildlife rehabilitation program. He has signs of surviving a fire incident, but turtles have amazing abilities to heal.”

As for his appetite, let’s hear from Dr. Julie Swenson.

“Alastor still doesn’t have the best appetite (the week after the exam), but he’s started to perk up in his behavior during some trips into the sunshine,” Swenson said. “We still have steps we can take where his appetite is concerned, and it’s fairly common for box turtles to go intermittently anorexic like this. So far, he’s maintaining weight, which is key.”

The exam was initially attempted without anesthesia.

“He’s a relatively agreeable turtle who will let us hold his head for a cursory exam, but in order to open his mouth for a look and to do some other checking, it required anesthesia,” Swenson said. “Luckily, he was very tolerant of the anesthesia. It often takes a lot longer for reptiles to wake up, but not him in this case.”

Alastor actually is not Swenson’s smallest patient.

“We’ve done surgery on tarantulas before,” she said. “We’ve examined Madagascar hissing cockroaches at the clinic. Technically, the bare-eyed cockatoos weigh less than Alastor. He’s towards the small end of the spectrum though.”

Have you ever considered a turtle’s respiration?

“We try to be careful and precise with everything, but you definitely have to be more aware of slight changes when examining a very small animal,” Swenson said. “For example, it’s hard to see when Alastor is breathing and that requires close attention. Reptiles are fairly prone to not breathing under anesthesia, so we have the ability to breathe for him if he needs it.

“That’s why we intubated him and gave him intermittent breaths. As a reptile, he doesn’t need near as many breaths as a mammal.”

On that note, there are significant differences between the respiratory systems of a reptile, a mammal, and a bird.

“Reptiles have a wide variety of lung structures – from very simple to more complex, depending on the species,” Swenson said. “All mammals have very similar lung structure to one another – their lungs expand along with their diaphragm. Reptiles and birds don’t have a diaphragm, so they actually use the movement of their chest wall to move air through the respiratory system. And in the case of birds, they have a series of air sacs which hold the air, so their lungs themselves are actually static and don’t expand or contract at all.”

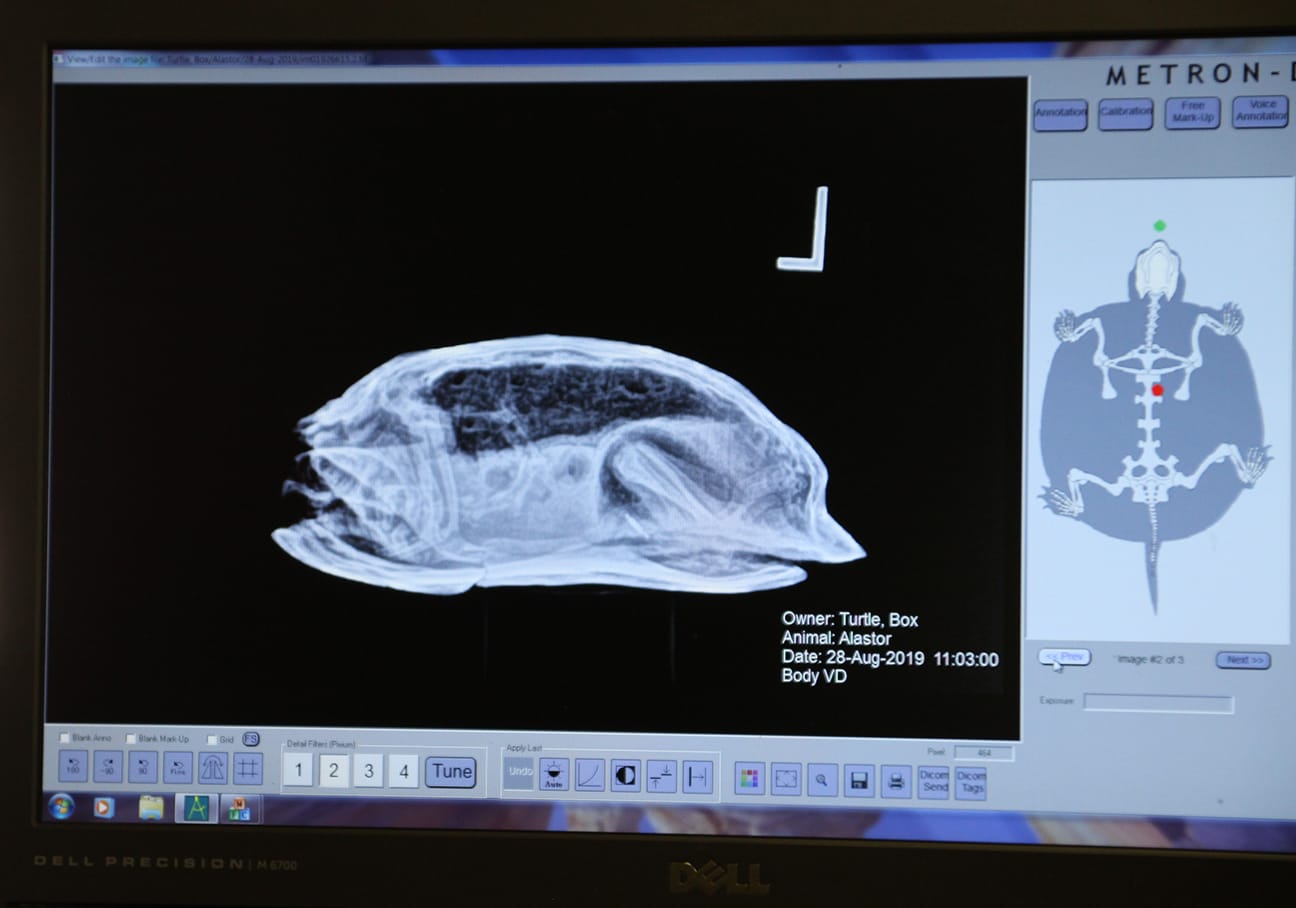

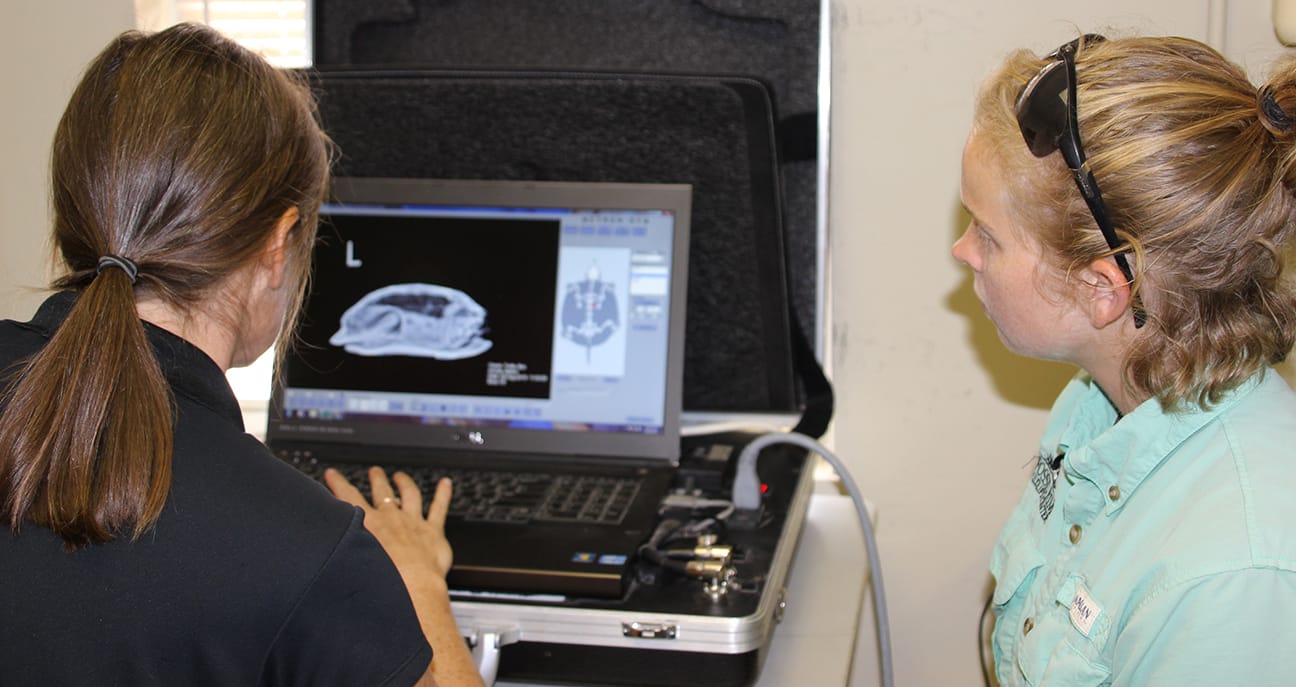

The technique to X-ray Alastor was different than the procedure used for other Fossil Rim species – see the related photo.

“All of our animals can benefit from radiography because you can see so much that you can’t see with the naked eye,” Swenson said. “But, you have added difficulty with a turtle or tortoise due to the shell. You can’t palpate a turtle like you would do to a mammal. So, the added diagnostics like radiography are even more important for an animal with a shell.”

Swenson and Dr. Holly Haefele make it a point to understand the anatomy of a vast array of Fossil Rim species, which is very beneficial to veterinary preceptees like Daniela Monje.

“If you do zoo medicine, the point is to know at least a little bit about a lot of animals,” Swenson said. “If any given type of animal is presented, you hope to have a basic knowledge to be able to work with it. That means a lot of reading on your own time, follow up with the literature to try to stay current, and have a familiarity with all types of animals you might see.

“A lot of vet schools focus primarily on domestic animals – so mammals and maybe poultry if you’re lucky. That’s why we have fourth-year vet students come stay at Fossil Rim – so they can get experience with a lot of these exotic animals you don’t see in school. That way, they get more comfortable with them and decide if working with those species is something they are interested in for later on in their careers.”

When Fossil Rim guests are actually in the park, as opposed to the Children’s Animal Center, their best chance of seeing a turtle are the red-eared sliders found in many of the watering holes. These are the most common aquatic turtles in Texas.

“Alastor does have a similar build to a red-eared slider, because both are turtles, as opposed to a tortoise,” Borgstrom said. “If you look at their toes, especially on their hind feet, you see webbing that allows them to swim. In terms of similarities to tortoises, Alastor does have a more tortoise-like shape with a high-domed shell compared to the flat shell of a red-eared slider, because box turtles do spend more time on land. He isn’t as strong of a swimmer, but can travel through water.”

Alastor also does not lean carnivorous to the degree of red-eared sliders, but both are omnivores.

“Most turtles will go after insects, insect larvae, and earthworms,” Borgstrom said. “A box turtle does eat more plant matter like vegetables and fruits. Alastor’s favorite fruit that we know of is blueberries. He also loves earthworms, hard-boiled eggs, and pinkie mice. The red-eared sliders will go for aquatic insect larvae, small minnows, and algae.

On a related note, Borgstrom really appreciates having Alastor when it comes to explaining turtles and tortoises to Fossil Rim visitors.

“Recently, we started doing programs where we take Alastor and our Texas tortoise, ‘Grady,’ to compare and contrast them,” Borgstrom said. “Sometimes, they each get snacks and we talk about their diet components. Texas tortoises eat a lot of succulents like prickly pear fruit and pads. Biofacts that we have, such as different species of turtle shells, are very helpful with educating, as well.”

With Alastor providing a valuable example – both for the Children’s Animal Center staff and the education department on outreach programs – to help children learn more about turtles, Borgstrom will watch him closely and revisit the veterinarians as needed.

-Tye Chandler, Marketing Associate

I am very interested in Alastor’s story because our Eastern Box Turtle, Yertle, just got over an URI; two weeks ago his x-Ray was 100% clear of his infection—but he’s eating very very little. Today I got 3 meal worms into him on two different occasions but it’s such a struggle. Just got crickets on Saturday, he ate one—I didn’t see him eat it, but the legs came out in his poop today. The last time he went to the vet—2 weeks ago, he had lost 5 grams of weight. Two days ago I saw him eat a bite of cantaloupe and a bite of strawberry—first time in several weeks, but that has been it for a long time. I offer him carrot, apple, blueberries, strawberries, red pepper, watermelon, some tomatoes, kale (which he won’t touch—ever.) I have heard that sometimes turtles stop eating for a while. His doctor has given him injections of Vit A and calcium. We have had Yertie for 23 years. But when I take him outside (I tape a balloon 🎈 on his back so I don’t lose sight of him)—he doesn’t stop, so full of energy and the need to explore. The next step, if he doesn’t start eating, his doctor says he will need a feeding tube—but she warns he might not survive the anesthesia! That is the last thing I want to do with him! Today he had two enormous poops with two cricket legs sticking out. I just hope and pray that his regular appetite will come back and I don’t have to force feed him. Worried!Help!

Hello, for turtle questions you could email our Children’s Animal Center Supervisor Kristina. Her email is kristinab@fossilrim.org